Pipe Tobacco

For most of the first 300 years after Europe’s discovery of tobacco (already agronomically well developed and widely cultivated by the native peoples of the western hemisphere for thousands of years) Europeans and their colonists consumed tobacco by smoking it in a pipe. [“Snuffing” powdered tobacco into the nose was considered a medicinal use, even though more popular among ladies and in the royal courts of Europe.]

Centuries old methods of packing, preserving and transporting tobacco from the New World to Europe by sailing ship resulted in chemical and physical changes in the tobacco that have come to be associated with characteristic classes of pipe tobacco. This is certainly true of Perique and of Cavendish tobacco (the Cavendish process, not “Cavendish cut”.)

Styles of Pipe Tobacco

For sampling the specific characteristics of a tobacco variety, it can be helpful to smoke a bowl of it unblended with any other tobacco. Sometimes you may just enjoy a particular tobacco all on its own. How enjoyable this is may depend on the acidity (pH) of the smoke it produces.

Flue-cured tobaccos yield relatively acidic smoke. By contrast, Perique produces relatively alkaline smoke. Increased acidity is the primary cause of tip-of-the-tongue bite. Increased alkalinity significantly raises the absorption of nicotine from the mouth and pharynx, and also can cause a bite toward the back of the tongue. So smoking tobaccos of identical nicotine content will seem stronger or weaker, biting or non-biting, depending on the pH of the smoke it produces. Virginia-perique combinations are popular specifically because these two components can be blended in a proportion (for example, 5 parts Virginia to 3 parts Perique) that is perfectly balanced‑eliminating all tongue bite while smoothing the apparent nicotine intensity.

Cavendish processed tobacco (not including commercial Cavendish doctored with polypropyleneglycol‑PPG‑or with glycerin) tends to be relatively neutral in pH, even when made from flue-cured Virginia leaf.

Most cigar varieties of leaf tend to be more alkaline, though considerably less so than Perique. Burley and some Maryland varieties start off with higher nicotine, and may also produce smoke as alkaline as that of cigar leaf. Dark-air-cured leaf is nearly always somewhat alkaline as well as higher in nicotine concentration.

A hallmark of so-called “English” style pipe tobacco is that it traditionally contained nothing but tobacco‑the result of a British law intended to crack down on adulterated tobacco in the market. This is no longer the law, but English-style blends certainly contain no added flavorings. So‑in its many variants, all are exclusively non-aromatic pipe tobaccos.

That restriction was accommodated by blending with a number of exotic tobaccos that, in themselves, are distinctly aromatic, such as fire-cured Latakia, and a number of varieties of Oriental (sometimes identified as Turkish) tobacco, each with its own aroma.

A classic Balkan blend contains flue-cured Virginia, Oriental, Latakia, and perhaps burley, Perique and sometimes Cavendish. These have a pouch aroma of smokiness and roasted nuts.

Other traditional English blends may utilize toasted, steamed, stewed or heavily pressed tobacco (Virginia or burley), and may appear entirely medium brown, rather than the bright and black pieces within a Balkan blend. All of the great tobacco purveyors of Britain (Rattray’s, Dunhill, etc.) have now outsourced their production to other European countries, and the blends are no longer the same.

These are blends of tobacco varieties that are flavored with non-tobacco flavorants, such as vanilla, chocolate, coffee, different fruits, or other natural flavors (e.g. licorice or anise, honey, molasses, Deer Tongue leaf, etc.). They may be flavored with brandy, rum, whiskey or other liquor or distilled spirit. Many of these flavorants evaporate fairly rapidly from tobacco leaf (though Maryland is known for its ability to cling to flavorants), so most commercial aromatic pipe blends include glycerin or polypropyleneglycol (PPG) or both, to retain the flavor.

Forming Pipe Tobacco

Most tobacco takes on a “sweeter” taste and more prune-like aroma when pressed. This is a combination of disruption of cell walls in the leaf lamina (which can happen at as low as 3 to 5 psi), allowing everything that is normally isolated within the cells to be exposed to both air and microbes. If this is done beneath a liquid seal (typically under about 35 psi), then the yeast, Pichia anomala, dominates, and turns it into Perique after a few months. With more access to air, that doesn’t occur so much, and there is less of a “barnyard” Perique aroma.

So just plain, dry pressing does alter the tobacco, making it somewhat darker in color (nicotine oxidation) as well as more fruity. Since there are infinite variations in the possible applied pressure and moisture content and ambient microbes, there are, like natural cheese, a lot of possible outcomes.

In the nineteenth century (say 170 years ago), several pounds of finished tobacco would be pressed under a screw-press into a thick sheet, to resemble a 1″ thick plank of dark wood. These were cut into flat, 1″ thick, 1.5″ wide bars of relatively dry tobacco, and wrapped that way, to be shipped to general merchants (trading posts and general stores). These rectangular bars were called tobacco “plug”. Each merchant had on hand a guillotine-type cutter (called a plug cutter), with a long lever for a handle, that enabled him to cut a plug of tobacco‑sold by the inch‑into the length desired by a customer. During that epoch, the customer would then take the paper-wrapped chunk of plug home, where it would store well, and later use a common knife to shave off slices for immediate use. This was called “sliced plug”. The sliced plug was then either broken into several large pieces, or rubbed between both hands, and transformed into shred, for packing into a pipe. Commercial vendors began offering pre-sliced plug (called flake) in small tins, and soon also offered “ready-rubbed” sliced plug, that resembles the typical shredded tobacco sold today.

A commercial alternative to plug tobacco was twist tobacco, which is a 1/2 to 1 inch thick rope of tobacco, sold as a roughly 1-foot length that had been twisted into a loop. Similar to plug, twist tobacco is first sliced, then the resulting coins either just folded and stuffed into a pipe bowl, or sometimes rubbed-out prior to packing the bowl.

A lot of this plug and twist practice really had to do with prolongation of shelf-life, shipping requirements within the commercial supply chain of the 1800s, and the consequent customer expectations at that time. The unique aroma and flavor characteristics that resulted from these processes were not likely the prime consideration for development of the techniques.

Press cake is a “plank” (1/2 to 1-1/2 inches thick after pressing) of tobacco blend that has been subjected to pressing. This can be accomplished at home by either neatly layering or randomly piling together stemmedwhole leafin a ratio that matches the desired blend. This can be done within a specially made, wooden press box, within a sturdy plastic container or tucked into a folded, 1-gallon Ziploc bag (unsealed). The tobacco is then subjected to pressure of at least 5 to up to 35 psi. This is fairly high pressure to create at home.The greater the length and width of the “cake”, regardless of its thickness, the greater the total applied weight must be.If you have a shop press or hydraulic jack, then this is not an issue. Just be aware that such a shop press or jack is capable of applying so much pressure that the pressed cake becomes too hard and dry, and nearly impossible to slice afterwards, without using a bandsaw.

If you intend to use a simple, lever-arm press with a weight on it, or to just stack a weight on top of the tobacco, then the dimensions of the cake should be kept small. For example, a cake that is 6 inches x 6 inches (typically 2-4 inches thick prior to pressing), has a surface of 36 square inches. So 36 pounds of direct weight (a 5 gallon bucket of water weighs ~40 pounds) would provide 1 pound per square inch (1 psi). The same weight on a lever-arm press that triples the effective weight would get you to 3 psi.

Occasionally, press cake with no added adherents (a casing that will “glue” the layers together) will hold together for slicing to flake or Cavendish cut. But if you want to assure that you will end up with durable slices, then a casing will need to be dispersed into the tobacco prior to pressing.

Depending on the amount of applied pressure, the pressing will need to continue for 1 to 6 weeks or so. The duration determines not only how well pressed the cake becomes, but also the degree of fermentation that occurs during pressing. The longer the press, the more fruity or prune-like the aroma becomes, and the darker the press cake becomes.

For sliced flake, cut the finished cake into bars that are about 1-1/2 to 2 inches wide. Flake is then sliced at your desired flake thickness. Cavendish cut is simply well adhered sliced flake that has been very slightly rubbed-out.

Roll cake is a pipe blend of whole leaf tobacco that has been rolled into the shape of a cigar, as tightly as possible. From among the leaf chosen for the blend, a suitable “wrapper”, maybe a contrasting color, is misted with non-chlorinated water, and allowed to reach high case. You may want to double or triple the thickness of the wrapper layer, in order to maximize the roll compression. The remainder of the pipe blend leaf is then gathered and cut (or torn) to a cigar length, and tightly rolled within the wrapper layer. You can use cigar glue to hold it wrapped, or just fold the head, and hold it in place with a wooden clothespin.

Some commercial producers of roll cake and sliced coins go to great lengths to assure that the cross-section of the coins will exhibit symmetrical patterns of contrasting color, and sometimes strategically located stem (running parallel to the axis of the roll cake), creating “bird’s eye” inclusions when sliced. You can give this decorative treatment a try, but it has no impact on the smoking quality of the coins.

The filler for this process should be in low to medium case, and can have a flavored or simply adherent casing dispersed into it prior to rolling, if you wish to produce solid, stable “coins”. The roll cake is allowed to age under its own wrapping pressure for 1 to 6 weeks. Coins are just thin slices of roll cake.

If you use no casing, the coins will come out somewhat crumbly, which may be just fine for smoking in your pipe.

A mechanical shredder can quickly produce shredded pipe tobacco directly from stemmed whole leaf. The width of the shred is specific to the shredder. Most commonly available tobacco shredders yield a shred that may be ideal for cigarettes, but too fine for your pipe tobacco preferences. A shred width of at least 1.5 mm is more suitable for use in a pipe. (Mechanically attempting to shred Latakia to a fine shred will result in a pile of dust and fragments.)

In order to manually shred pipe tobacco with a knife or chaveta, roll a “cigar” from whole leaf of the individual ingredients of the blend, or even of the final blend ratio. The narrower the gauge of the “cigar”, the finer the likely shred. A “cigar” diameter of about 3/4 inch produces a nice shred width, when sliced with a chaveta as thinly as is practical.

Select two or three sections of the leaf to rehydrate, for use as a wrapper, then tear or cut the remainder of the stemmed leaf to a length that will be wrapped by the chosen wrapper. Once the “cigar” is tightly rolled, attach a wooden clothespin at the head, to hold the wrapper in place, then flatten the cigar beneath your palm. Using a chaveta, rock the blade over the foot of the “cigar”, taking a thin slice with each pass. [If you use a traditional chaveta, you may want to cover the back edge with a section of plastic tubing or old garden hose, to serve as a handle, and allow you to apply more force to the blade comfortably.]

Once the “cigar” is sliced into a row of coins, use the chaveta to cut the entire row down the length of the row. Cut it into halves or thirds, in order to limit shred length.

The sliced, split coins are now gathered into your hands, and rubbed together to rub-out the shred.

Crumble cake is similar to press cake in its manufacture and appearance. You end up with a plank of pressed tobacco. The difference is that crumble cake is initially composed of tobacco that has already been shredded and blended. So it looks more like particle board. The purpose of a crumble cake is to prevent a pipe blend that would rapidly settle-out into its individual components from settling at all during storage and handling.

As an example, Cornell & Diehl Pirate Kake is 75% Latakia. Because of the difference in particle size and weight of the Latakia vs the other blend components, even minimal agitation leads to the “Brazil nut effect”, in which the larger pieces “float” to the top, with the tinier bits sifting out to the bottom. Pirate Kake is sold as a plank of crumble cake.

To smoke crumble cake, just break off a corner or chunk, rub it out in your hands first, or just directly crumble it into the pipe bowl.

Perique is tobacco that has been pressure-cured beneath a liquid seal, to keep out air completely. Perique can be made using any variety of tobacco, though the nicotine content will vary from one variety to the next, and cigar varieties may retain a residual cigar flavor.

It is made by pressing color-cured tobacco inside a liquid-tight container for 3 or more months. It requires the application of about 35 psi, which can be generated either by a shop press / hydraulic jack or using a hand-screwed carpentry clamp. The follower for the pressing container must make a close seal with the sides of the container, and this must be regularly checked to assure that a thin layer of liquid continues to provide a seal at the margins.

The dark color of perique is the result of oxidation of nicotine. The nicotine-rich solution is squeezed from the cells of the tobacco, but will not oxidize fully until the leaf is exposed to air. So development of the very dark brown color of finished perique requires that the pressed leaf be removed from the press a few times, at intervals of weeks, during the months of pressing, and spread out to air for 10 minutes or longer, before being returned to the press, and brought under pressure once again‑adding a bit of water to restore the liquid seal, if needed.

Perique requires moderately cool ambient temperatures (between 50 to 80 degrees F) for the desired microbe (Pichia anomala) to dominate the fermentation. Perique will initially produce a stinky aroma which, after the first few weeks, will change into a prune-like, fruity aroma. [Perique fermentation, if allowed to reach higher temperatures (say 100°F+ in a shed or attic) may allow dominance of coliform bacteria, and produce a fecal aroma that might require a year or more to dissipate.]

After 3 or more months of pressing beneath the liquid seal, perique comes out of the pressing container quite soggy. It can be stored in this state in a vacuum-sealed container indefinitely, with little risk of spoilage. Once opened, it is best to refrigerate it.

The alternative storage for perique is to spread the leaf, and allow it to mostly dry out. Then roll it into a “cigar” of perique, slice it into a shred of desired width, and store it as you would any other pipe blending ingredient.

Cavendish tobacco is literally cooked tobacco or stewed tobacco. It’s origin is likely in 18th century shipping of massive, sealed hogsheads of tobacco within the sweltering holds of sailing ships, as they crossed the Atlantic.

Making Cavendish processed tobacco is similar to canning green beans. Damp (not dripping or soggy) whole leaf is packed into a canning jar, capped, then pressure-cooked. It requires 5 to 8 hours of 15 psi pressure cooking (at sea level) to complete the process.

Any tobacco variety can be made into Cavendish. Burley, flue-cured Virginia and Maryland tobacco are good candidates. Which you chose will impact the aroma as well as the nicotine content. Cigar varieties will retain a cigar tobacco quality after Cavendish processing. While the leaf can be processed with the entire stem intact, or stemmed entirely, it is more convenient to frog-leg the leaf first, so that it packs into jars easily, and when it’s done, it simply needs to be shredded.

Cavendish tobacco may come out of the process appearing black, but once adequately dried to low case for storage, it will take on a light to deep brown character. (Commercial “black Cavendish” remains black only because of the polypropyleneglycol (PPG) that is added to it to keep it both black and squishy.) If you make Cavendish, then store it moist enough to remain black, it will promptly mold (unless you add polypropyleneglycol [PPG], which will retain the dark color, while acting as an anti-fungal). Cavendish definitely smokes better without PPG.

Cavendish-cured tobacco is generally smoother and milder than the same leaf prior to processing.

Twist is tobacco leaf that has been twisted into a rope. Depending on the region of the world, twist is made with either air-cured leaf or with well-wilted, green leaf. The overall moisture content should be low to medium case, so that it does not mold in the center. Using either brown or green leaf, the subsequent fermentation within the twist usually requires several months to run to completion, ultimately turning the tobacco dark brown to black.

The compression and tension of twisting disrupts the cells of the leaf lamina, spilling their contents to the leaf exterior. A combination of intrinsic leaf enzymes (oxidase, peroxidase) together, perhaps with microbes (predominantly yeast likePichia anomala, or even common yeast used for bread or beer making, but ubiquitous in the air) oxidize the proteins and carbohydrates, and ultimately provide a prune-like aroma. As with any open microbial fermentation, it would be subject to unexpected, odd or undesirable outcomes.

Twist is sold in some parts of Brazil by the length the purchaser desires. Its uses include pipe blending (or straight), cigarettes and smokeless. Typically, a pocket knife is used to shave off a slice, which is then rubbed-out to a shred.

Approaches to Pipe Blending

If you already have an idea of the kinds of pipe tobacco that you like, or the specific ingredients of pipe blends that you enjoy, then making your own blend is a simple matter. Getting is just right, with the right pouch aroma, the right strength and aroma fullness…these are more challenging, though still not difficult.How you begin will depend on whether you already have specific ingredients that you need to work with, or instead, can obtain any ingredient that you think you might want to use. How you do measurements and document them can make the process of blending tedious or a delight‑complicated or simple. Some folks use a precision scale (accurate to tenths or hundredths of a gram) to carefully weigh out their blend ingredients. This is admirable, but is far more consistent than the tobaccos that will be blended. The exact character of a tobacco ingredient may change from one purchase to the next. It’s an agricultural product. It varies.

If your ingredients are roughly in the same shred size (and degree of “fluffiness”), then you can measure by volume. That is, you can just count tablespoons (level or heaping or whatever, but be consistent) of each ingredient, and document that. An ounce to an ounce and a half (weight) of tobacco blend is about 16 tablespoons of ingredients. It is not unreasonable to bend in increments of 1/16 of a batch‑1 part per 16. Sometimes, you may recognize the need to be more delicate, and measure using a half-tablespoon (32 of them for a test batch), but that is surprisingly uncommon. [The late Craig Tarler of Cornell & Diehl recorded many hundreds of pipe blend cards with blend ingredient measurements of 16ths, considering it in terms of ounces per pound of blend.]

However you go about measuring the blend proportions, write it down, either on the exterior of the Ziploc bag that contains the final blend, using a Sharpie, or on a note pad. You will likely need to refer to it for the next test blend.

Known components

If you can obtain whatever ingredient might be called for, then go to popular websites that sell or review commercial pipe tobacco, and see what information is available on a blend you know you like. While that will probably not provide many meaningful proportions, it may be enough of a clue to get you started. Plan to make very small test batches of about 1 ounce of blend. If you have no clue about relative proportions within the target blend, then begin with equal proportions of each ingredient. Smoke a bowl. If a batch seems close, but not quite there, consider which ingredient seems to be underrepresented, which might be overstated. Make only a tiny adjustment for the next test batch.

Working with the tobacco you already have

Begin your trials by smoking a separate bowl of each available ingredient straight. (You probably don’t want to do that with Latakia or perique.) But get to know the characteristics of the potential ingredients. Take notes.

- does it cause tongue bite?

- front or back of the tongue?

- how potent does the nicotine seem to be?

- what is the overall fullness of the flavor and aroma?

- is it sweet? bitter? sour? peppery?

- is it enjoyable straight?

In blending what you have, one approach is to bring together ingredients that compliment one another in their answers to the above questions. Another is to attempt to amplify certain qualities by combining two or more ingredients that seem to feature it.

This kind of pipe blending is a truly blank slate. You are the only judge as to whether or not a blending test batch is better than one of the individual ingredients alone.

Remember that with any air-cured or flue-cured tobacco you might have, you can turn some of it into Cavendish and some of it into perique, if you don’t already have those components.

Blending hints

Burley and Maryland will tend to increase the potency of a blend, in both throat hit and nicotine. Burley contributes its distinctive aroma, while Maryland is fairly neutral in aroma.

Oriental leaf usually diminishes the nicotine strength, may add subtle floral notes, and may contribute a bit of sweetness. All of these factors differ by Oriental variety.

Flue-cured Virginia tends to lower the total nicotine, brighten the aroma and feel, and counter some of the throat hit of burley. Darker Virginias are fuller and slightly less acidic. The lower pH (greater acidity) of flue-cured tobacco contributes to tip-of-the-tongue bite.

Dark-air-cured leaf significantly amps up the nicotine and diminishes the bite of flue-cured. In that regard, it can fully replace the need for perique, though it contributes a quite different aroma.

Perique adds a full, rich, deep aroma to a pipe blend. It can completely eliminate flue-cured tongue bite, but if used in excess, can create its own back-of-the-tongue-bite, and dramatically increase nicotine absorption from the blend. A starting point for pH balancing flue-cured with perique is to add perique to the blend in a proportion of about 3 parts perique to every 5 parts of flue-cured. Adjust your preference from there.

Latakia adds a full, smoky aroma, but one that is more like a somber incense, rather than barbecue. By weight, it tends to lower the nicotine concentration of a blend. Typical Latakia proportions range from about 15% up to 50%, though some commercial blends go as high as 75% Latakia. A middle of the road Latakia blend will have between 25% and 35% Latakia. As the proportion of Latakia increases, so does the vague taste of what is described as “soapiness”, as well as a sense that your tongue may have been used as a doormat. Very high Latakia concentrations (50% on up) are often reserved for the last bowl of the evening.

Cigar leaf in a pipe blend usually refers to a small proportion of maduro leaf from Pennsylvania Broadleaf, Lancaster Seedleaf, or a similar, American variety. This broadens the flavor profile, and adds a touch of sweetness. Using leaf from most Caribbean (e.g. Habano) cigar types will cause your pipe to smell like a cigar butt.

If your ultimate goal is to create a plug or even an aromatic blend, you should settle on a happy blend before the additional processing or flavoring.

These are only a few examples of pipe blend recipes. The “frog” series is exclusive to WLT.

Black Frog

a robust Balkan blend

- Latakia 43.5 %

- Virginia Bright 37.5%

- Perique 18.75%

Calico Frog

a milder Balkan blend with full Perique

- Latakia 18.75 %

- Virginia Bright 43.75%

- Perique 37.50%

Top Frog

English-style Oriental blend

- Virginia Bright 50.0%

- Perique 30.0%

- Stacked Basma 20.0%

Curiosity

A rich, American burley blend

- Burley 36%

- Virginia Red 23%

- Fire-cured 23%

- Perique 18%

Skree

a basic Virginia / Perique blend

- Lemon Virginia 62.5%

- Perique 37.5%

The book, Blend Your Own Pipe Tobacco: 52 recipes with 52 color labels is available to purchase through this link at wholesale price.

These whole leaf blend kits include various tobacco leaf components that can be shredded and blended in the same ratio that is provided, or adjusted in any way you like. They are shipped with a little spray bottle of casing, specially designed for enhancing the tobacco for cigarette use. You can try the casing on a small batch, to see if you prefer the blend with or without casing. These casings do not render the bend sticky or even what might be considered “aromatic”.

The Balkan Tradition kit is surprisingly close in character to the now extinct pipe tobacco blend, Balkan Sobranie Smoking Mixture (Balkan White). Experimenting with it is an excellent way to begin exploring English-style Balkan mixtures.

For pipe blending, you may prefer to shred the leaf to a coarser shred than for cigarette use.

Flavorings and Sauces

There are four general categories of casings for pipe tobacco:

- Sweetening

- Flavoring

- pH (acidity) modifiers

- Humectants

Some of these play multiple roles. For pipe tobacco made from excellent quality whole leaf that has been properly blended, the need for casings may be limited to attempts to create “aromatic” pipe tobacco‑sweetening and flavoring.

If you decide to add casing to your whole leaf tobacco blends, be sure to shred the tobacco first. It gets sticky! If you press your cased tobacco blend, purchase some baking parchment from the grocery store, and use it to line the pressing container and follower, again to prevent sticking.

Free Tobacco Flavoring Book: An entire 74 page book on tobacco flavorings (from Leffingwell, Young and Bernasek [R.J. Reynolds], 1972) can be downloaded for free from Leffingwell.com: Tobacco Flavoring for Smoking Products. It contains an extensive list of specific chemicals and compounds evaluated for this use, including their smoke taste as well as smoke aroma.

“Materials such as Orange, Lemon, Patchouli, Rose, Neroli, Tonka, Deer Tongue, Vanilla, Valerian, Orris, Bergamot, Cardamon, Cinnamon, Coriander, Cedarwood, Mace, Lavender, Cascarilla, Sandalwood, Lovage, Styrax, Balsam Peru, Balsam Tolu, Foenugreek, Rum, and Geranium are old favorites.”

“The use of any given flavoring material is dependent upon several factors:

1. Is the material readily available at reasonable cost?

2. Does it blend well and enhance the smoking flavor of the specific tobacco base to which it is added?

3. What is the optimum use level?

4. What is its effect on package aroma?

5. Is it stable on storage?

6. Is the method of applying the flavoring material to the tobacco base compatible with acceptable manufacturing operations?

7. Is the material safe from a toxicological standpoint?”

Sugar, if burned, tends to caramelize and char, and give up an acrid smoke. There are two types of “sugars” used for casing, reducing sugars and non-reducing Sugars. [Much of the commentary on sweetening is from FTT forum member, Jitterbugdude, from Maryland.]

Reducing Sugars

glucose, fructose and invert sugar

These are considered more chemically reactive than non reducing sugars

Non-reducing Sugars

sucrose (white table sugar and brown sugar)

Reducing sugars react with the free amino acids (FAA) in the tobacco leaf as well as with the FAAs from other substances such as cocoa and licorice. These are very pH dependent. The reaction is usually not a complete reaction so a secondary casing is often added. This is where the non reducing sugars come in to play. Brown sugar or regular white sugar are often used.

Non-reducing sugars caramelize more than reducing sugars. Common table sugar can be converted to a mixture of fructose and glucose (both reducing sugars), by heating a sugar solution with lemon juice or citric acid, as is sometimes done while making jellies or jams.

Honey

Honey is mostly reducing sugars‑a mix of glucose and fructose. The ratio changes depending on the type of honey.

Molasses

Molasses (known also as treacle) is a residual product from the manufacture of sugar from sugarcane or sugar beets, and is sold in a wide range of consistencies and composition. As a rough average, molasses from the grocery store consists of:

- sucrose 30-35% non-reducing

- invert (glucose and fructose) 30% reducing

- other compounds and water 35%

In addition to serving as a sweetener, it adds favors, and also serves to some extent as a humectant.

Maple Syrup

Maple Syrup is, like molasses, a mixture of several sugars, flavors and water.

Artificial Sweeteners

Artificial Sweeteners may or may not make sense for oral tobacco (chew, for example), but their addition to tobacco that will be burned is not a good idea. Most artificial sweeteners break down chemically when heated, meaning there is no sweetness contributed to the smoke. Some even produce toxic chemicals when heated.

Flavoring can be derived from all manner of natural products, from foods and beverages to herbs and spices, to oils and liquors. The form in which such flavors are added to a tobacco casing makes a difference. As an example, cocoa or chocolate are a commonly used tobacco flavorant. But if you simply add cocoa powder to tobacco, it inhibits burn, and tastes unpleasant. Instead, chocolate or cocoa flavoring, in the form of a specialty liquid, is added.

Liquid concentrates of a host of different flavors are available as essential oils (not water soluble) or as water soluble, in a solution of polypropyleneglycol (PPG). One source for both of these types of flavorants is LorAnn Oils, which offers a huge selection. Generally, oil-based flavors will need to be dissolved into a bit of alcohol (e.g. vodka), which will then allow it to be dissolved into water. PPG-based flavorings are readily soluble in water.

Usually, only the tiniest amount of a flavor concentrate is better in casing than so large a quantity that the specific flavor can be immediately identified. Subtle flavoring produces a vague enhancement of the smoke aroma, while a strong dose shouts out its name [Some of the “fruit” flavored pipe tobacco blends from Cornell & Diehl, such as “berries”, “apricot” or “peaches and cream”, while delicious, do not actually taste identifiably like the named flavors.]

Modification of tobacco pH (a lower number means more acidic, while a higher number means more alkaline) causes changes that can be grouped into two general categories: chemically altering amino acids and other compounds within the tobacco or tobacco casing, and directly altering the acidity of the smoke of combustion. Citric acid solution, for example, is commonly used as a casing on flue-cured tobacco to “smooth” away the “harshness”, though what exactly this means is unclear.

In contrast to using the more alkaline nature (higher pH) of perique smoke to neutralize the relative acidity (lower pH) of flue-cured tobacco smoke, directly adding acid or alkali chemically removes (or alters) some offending compounds.

The character of a humectant is that it tends to attract and hold onto water. Similarly, a humectant may hold onto a flavoring ingredient which might otherwise promptly waft away. Honey and molasses (and other syrups) serve to some extent as humectants.

Glycerin and polypropyleneglycol (PPG) are the most common humectants used in commercial pipe tobacco. Not only do they (alone or in combination) hold onto moisture, keeping tobacco eternally soft and “consumer-friendly”, they also do the same with flavorants.

In addition, PPG exerts a mild, anti-fungal effect, decreasing the risk of mold developing. For this latter reason, PPG is added to every commercial pipe tobacco on the market today. Even brands noted for being initially on the “dry” side contain some PPG. Glycerin is anti-bacterial.

Unfortunately, some pipe smokers can easily taste PPG. Regardless, PPG compromises the burn properties of a tobacco blend, and is the primary cause of a gooey, tar-like mess created in a pipe stem and at the bottom of a pipe bowl. Natural, PPG-free pipe tobacco simply doesn’t do that.

For a pipe blend that contains no humectant, storage within a vapor-proof container (not a common, pipe tobacco tin) will maintain its current moisture for weeks or months. If it becomes too dry, then flicking in a few drops of water from your fingertips, and then re-closing the container will restore the tobacco to a higher state of case.

Earl Grey

A casing with a drop each of bergamot and lavender (LorAnn Oils) into a 1/4 teaspoon of glycerin and a 1/4 cup of vodka and 1/2 teaspoon of invert sugar and added that to 100 grams of my Cavendish and put in a press for 3 weeks. I tried some after cutting and drying it and what an awesome flavor. It truly tastes like Earl Grey. It is rather strong in flavor and will benefit being blended.

[chillardbee]

Below are two recipes for casing during the pressure cooker Cavendish procedure.

Unflavored Black Cavendish

Glycerin at a 1:20 to 1:40 ratio by weight of glycerin to tobacco, before pressure cooking. This is not a precise procedure to begin with, but for the sake of making it simple, this involves about 20 parts tobacco, 19 parts water, and 1 part glycerin. Then pressure cooked in a sealed jar at 15lbs for 3 to 4 hours. If this done with a flue cured bright tobacco, dried, and aged a month, it makes a sweet but tobacco flavored black Cavendish.

[ChinaVoodoo]

Vanilla Black Cavendish

Follow the black Cavendish procedure (above) but use vanilla extract. This means 20 parts tobacco, 10 to 15 parts water, 5 to 10 parts vanilla extract. It must be an alcohol based vanilla extract.

[ChinaVoodoo]

Berry-infused tobacco

Roll tobacco into a rope. Pack into a jar. Fill jar with dried elderberries or dried currents. Put some water in. Bake at 220°F for a couple hours.

[ChinaVoodoo]

Toasted Burley

- Combine 1 Tbsp Hershey’s syrup (may also use molasses if preferred or a combo of both) per 1 ounce of water (distilled preferred but not necessary)

- Spread your Burley out onto a cookie sheet and preheat oven to approximately 180°F.

- Toast the tobacco until almost dry (not crispy) and remove from the oven.

- Spritz the Burley with casing solution, mixing well, until covered but not dripping wet.

- Place the tobacco back in the oven and dry again.

- Repeat these steps 3 or 4 times.

[Cobguy (Darin)]

“Coffee House” Red Flue-cured Virginia (FCV)

- Combine 1 Tbsp Apple Cider Vinegar (Bragg’s) per 1 ounce water (distilled preferred but not necessary) and add 1/8 tsp cinnamon.

- Spritz whole Red FCV leaf while in low case until it’s brought to high case.

- Allow the leaf to dry back down to medium case and make a stack.

- Press the stack into a plug using your home-press of choice for at least 3 days.

- Slice into flakes and jar for at least 3 months. 9-12 months is better.

[ Cobguy (Darin)]

Pipe Tobacco Basics

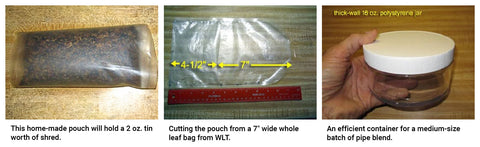

Once you have prepared a pipe tobacco blend, and brought it to your desired case (degree of humidity), an ideal container is one that is transparent (so you can see what’s in there), relatively vapor-proof, and informatively labeled. These requirements can be met by a number of kinds of containers. And if you disregard transparency, even more kinds. The classic tobacco tins in which small and large quantities of pipe tobacco are sold are not transparent, not vapor-proof (once opened), and simply provide a known name of the blend, but not its composition.

If, on your chosen container, you clearly identify the recipe, either by writing directly on a bag, or taping a paper label onto other containers, then multiple variations of a blend you may be experimenting with will be easy to keep straight. A colorful, printed label, such as those shown in the pipe blend recipes section, and taped onto a container, can also add an inviting aspect of graphic art to your your blend.

Ziploc bags are commonly available. A “freezer” Ziploc provides a more effective vapor barrier than a sandwich bag. Depending on ambient conditions, a sandwich bag may be adequate for storage for a week or two, whereas a freezer bag may keep the tobacco from drying for a month or two. The difference may be meaningless for tiny test batches.

Ziploc tubs, and similar, small food containers are available with tightly-fitting, snap-on lids. They come in a dozen different sizes and shapes, and work fairly well for pipe tobacco.

WLT tobacco bag pouch: If you happen to receive some whole leaf from WLT that is contained within a 7-inch wide bag, you can trim the empty bag with scissors to make a handy, effective pipe tobacco pouch.

If the pouch apron is long enough, the pouch will remain well closed without using tape. And the apron serves as a convenient spot to pack your pipe, allowing any fallen tobacco to glide back into the pouch.

Plastic jars with a good lid seal are wonderful for holding a medium-size batch or larger, and allow a graphic label to be removably taped to the lid.

The wider the lid of a jar, the easier it is to pack a pipe from the jar.

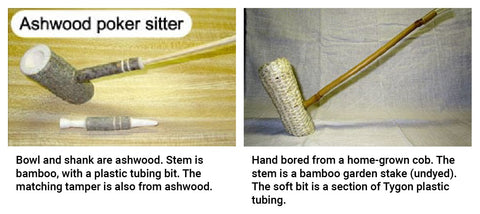

A pipe is just an object with a big hole into which to stuff pipe tobacco, and a smaller hole from which to draw out the smoke from the bottom of the big hole. Pipes have been made of any material that can withstand the combustion temperature of tobacco: glass, ceramic, clay, mined mineral (like Meerschaum), stone of various sorts (e.g. soapstone), many varieties of wood, some plastics (Dr. Grabow “Brylon” pipe bowls are made with nylon that has been blended with briar dust.), and of course, corncobs. Wood pipes, made from nearly any non-toxic hardwood, are available with and without the tree bark still on. The stems can be made of acrylic, hard rubber, bamboo or any other suitable material that can provide an enclosed, stiff tube.

Most pipes found in a tobacconist will be made of briar root. This is the extremely hard root of a Mediterranean heather shrub.

Ash is unique in that the pith of the branches, both large and small ones, is soft and spongy. This can be cleanly removed by passing a hot wire or rod through it. This also means that the bottom of the bowl should be lined with a spackle of 50% plaster of Paris: 50% fine sand, to seal and fire-proof the pith there.

The center of a corncob is hard and woody, when fully dried. Nearly every cob can be made into a pipe, though a nice internal diameter bowl requires a particularly broad cob. Some of the varieties of corn with the largest ears do not provide the fattest cobs. The cob shown below is from an ear of Boone County Kentucky field corn.

Corncob pipes are easy smokers, requiring no break-in period, and are available ready-made at very low prices. Some pipe smokers contend that they smoke better than briar pipes, though their lifespan in shorter.

Of course, a variety of ready-made corncob pipes are available for purchase from Missouri Meerschaum as well as other manufacturers, typically at 1/4 to 1/10 the price of a common briar pipe.